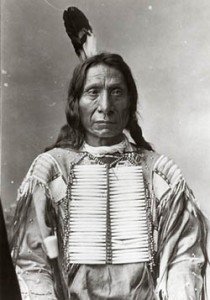

There is no photograph of the Sioux Chief Crazy Horse. He didn’t allow them. The day after he was killed on Septemeber 5, 1877 at Fort Robinson in present day northwestern Nebraska, his body was turned over to his elderly parents. They took his body to Fort Sheridan where it was placed on a scaffold until the remains were moved, along with the Spotted Tail Agency, to the Missouri River. To this day, nobody knows for certain where Crazy Horse was ultimately interred.

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!

The story of Crazy Horse’s months after the Battle of the Little Bighorn is one of both battles and retreats from the approaching cavalry forces. His surrender and subsequent killing at Fort Robinson may very well not have occurred had he not been persuaded to give up the fight by fellow Sioux leaders.

The Aftermath Of The Battle of the Little Bighorn

When the U.S. Cavalry answered the defeat of George Armstrong Custer, the Native Americans who had participated in that battle and others were on the run. The increase in troop deployments and pressure placed those Indians who had deserted the reservations over the prior year in a no win situation. Some did return to their reservations but many others didn’t. In the case of Sitting Bull, the overall leader and strategist of the 1876 war, he was not to be found and eventually fled north to Canada with several hundred followers. He obviously was a very wanted man but was out of the grasp of the U.S. military. The immediate aim of the the U.S. government was to somehow put the renegades back on their reservations. This seemed to be the plan as opposed to planning more retaliatory attacks.

When you research the legend of Chief Crazy Horse, you will find several different versions as told by more than a half-dozen Native Americans. Most of the stories come from Native Americans who actually knew Crazy Horse. These are thought to be reasonably reliable. I think some of the more unreliable sources might have come from the press of the era who embellished details of many a battle. Among the accounts from Native American witnesses, all pretty much agree that Crazy Horse was both a talented and brave warrior and was greatly respected by his fellow Indians. Where some of the differences lie are in accounts of battles and how involved or uninvolved Chief Crazy Horse was in any particular one. The fact that he was a proven warrior and was strongly against being put on a reservation seems to have the agreement of all who recalled him.

A Prelude To Surrender

The Great Sioux War of 1876 marked the turning point of what had been decades of conflict between the U.S. government and the Native Americans of the western plains. The Sioux uprising of that year had many causes and the battles that ensued, including Custer’s Little Bighorn defeat, set the stage for an all out effort to by the U.S. Army to once and for all place all Native Americans back on their reservations. The frontier line westward expanded with every year and the transcontinental railroad had been completed about eight years prior.

With Sitting Bull in Canada, the priority was to capture Crazy Horse. At this point Crazy Horse represented the strongest and most influential anti-reservation hold out. While there were factions within the renegades that simply wanted to give up the struggle and return to the reservations, Crazy Horse would have been the galvanizing force for continued resistance and the U.S. military knew this. They knew it through discussions with those that did return including Sioux who were close to Crazy Horse. The key to putting an end to the standoff was to either outright capture Crazy Horse or somehow convince him to surrender.

Attempts at Surrender

Amazingly, there were several attempts made by both the U.S. Army and the Sioux themselves to surrender. The book, Crazy Horse, The Life Behind the Legend, authored by Mike Sajna, describes efforts made by General Nelson Miles, General George Crook and the renegade Indians to effect some sort of surrender at about the same time. Apparently, the relationship between Miles and Crook was not the best. Author Mike Sajna points out that there was a bit of a rivalry between Crook and Miles in as much as whoever effected the surrender would be thought of as arranging the end of the Indian Wars.

While Chief Crazy Horse’s surrender would certainly be significant, it wouldn’t signal THE end of conflicts. Crook was working out of Omaha Nebraska with frequent trips to Fort Robinson in today’s northwest corner of Nebraska. General Miles and his troops were gathered north of the suspected Sioux encampment in the Powder River area. It was Miles troops who were in striking distance for any offensive action.

Native American couriers were sent to find Crazy Horse and offer surrender terms. The couriers were sent by both Miles and Crook separately. The terms were fairly the same however. Unconditional surrender and return to the reservation. The couriers were sent it was believed not only to deliver the terms to Crazy Horse and the leaders with him but also to pinpoint exactly where the Indian encampment was.

There is also a story in the aforementioned book regarding Crazy Horse where a small delegation of renegade Indians were dispatched to find General Miles as a feeler for surrender terms. Reportedly, the group encountered Crow Indians during their journey and were attacked. The Crows and Sioux had been bitter enemies for some time. Many of the Crows including the group involved in this attack were used by the U.S. military as scouts. Crows were used as scouts as part of Custer’s 1876 expedition. This was but one reason for the bad blood between the two tribes.

While General Miles deplored the action when he learned of it, in fact he had directed the Crow not to interfere with any Lakota messenger, the Sioux took this Crow attack as an invitation for more hostile action. What resulted were some relatively minor skirmishes but nothing like an all out war. For one thing, many of the remaining Sioux and Cheyenne were tiring of war. One battle that occurred after the Crow-Sioux clash between Miles’ troops and the Lakota Sioux was the Battle of Wolf Mountain on January 8, 1877. As was typical of most of these clashes, the Indians fought individually while the army troops fought more as a coordinated unit. The results were two soldiers killed, and on the Indian side, one Cheyenne and two Lakota slain.

From later accounts from Native American participants, by the spring of 1877 and after skirmishes like the one at Wolf Mountain, it was felt throughout the camp that a surrender would have to take place regardless of the terms set forth by the U.S. Army. It was a choice between starvation and constant moving or the reservation and food and clothing. This is essentially what was written years later by participants.

The Surrender of Crazy Horse

The actual surrender of Crazy Horse and thus of his followers would be plagued with fits and starts. The offer from the U.S. included of course food and supplies and relocation to a reservation. While the leaders within Crazy Horse’s group would meet and discuss the pros and cons, Crazy Horse himself was usually absent. He was a known holdout and wasn’t interested in the details, all of which he already quite knew. He was known to be agreeable to whatever the group decided although he personally struggled to accept it. It was only after much coaxing that he decided to go along with the vast majority but even after that he wavered to some degree. He was described by some later as being depressed. It was facing the inevitable that caused him grief. It would turn out to be a disgruntled surrender.

In the end it would be a negotiation as to where to resettle. Crazy Horse was known to have his opinions as to where a reservation should be located although the military was dead certain where it would be. Crazy Horse suggested a location near present day Gillette Wyoming. The military said that was out of the question. Crazy Horse dreaded the possibility of being resettled to the north near the Misssouri River.

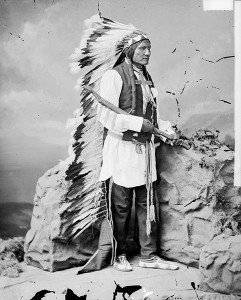

The winter of 1876-77 took it’s toll on the starving renegades who at one time had to eat their ponies after they perished. Since April of 1877, the Sioux Chief Red Cloud had been in the Powder River region trying to convince Crazy Horse to surrender. This was the same Red Cloud who reigned over what was called “Red Clouds War” during the latter 1860’s and successfully caused the U.S. to close three forts along the Bozeman Trail. This was also the war that resulted in what is referred to as the “The Fetterman Massacre“. By the time the military asked for his assistance in 1877, Red Cloud had adapted to the reservation life. Red Cloud would have to solicit the help of other Sioux and Cheyenne leaders encamped with Crazy Horse in an effort to bring about a peaceful surrender.

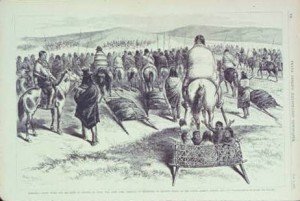

The end for Crazy Horse as a free Indian came on May 6, 1877. Red Cloud’s efforts succeeded. On this day, about ten months after the Battle of the Little Bighorn, an army detachment from Fort Robinson traveled to meet up with Crazy Horse along with a forward cavalry group that had left the fort five days previous. The meeting with Crazy Horse was to be handled by a Lt. William Philo Clark. According to Crazy Horse, The Life Behind the Legend, by author Mike Sajna, along with Clark, who was known to the Indians as White Hat, were twenty Cheyenne scouts and a reporter from the Chicago Times. Lt. Clark found Crazy Horse sitting on a blanket at the meeting point. Also there were Red Cloud and He Dog, another Lakota Sioux leader.

After asking his command to stay behind a distance, Clark went up and sat down beside Crazy Horse, facing him. The meeting was actually opened by He Dog, a Sioux chief, who presented Lt. Clark with a shirt and war bonnet. Crazy Horse had already given his war shirt to Red Cloud. Some thought that in this way, Crazy Horse was surrendering in fact to Red Cloud and not the white men. This was most likely symbolic although important to Crazy Horse. He Dog was reported to also have given up his war-horse and saddle to White Hat. There was not a recording of what exactly transpired between the two men but according to Sajna the discussion would most likely have been about the location of the reservation. This was the point that was still somewhat unsettled. Crazy Horse was said to be agreeable to a site just east of Fort Robinson since his other choice in Wyoming had been turned down. The meeting with Crazy Horse lasted some five minutes and the Times reporter noted that all seemed to go well and appeared to be genuine. The only reported words from Crazy Horse at this meeting was that he uttered ” I have given all I have to Red Cloud”.

The meeting was over by noon and the Chicago Times reported that the group began it’s march eastward toward the Red Cloud Agency. The Red Cloud Agency is about one mile west of the present town of Henry Nebraska. The troops and scouts led the way followed by Crazy Horse and his people about a quarter mile behind. The Chicago Times described it as an organized military march.

Two additional articles you’ll find interesting are the relationship between Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill Cody and on our Western Trips site, the Battle of Slim Buttes that occurred after the Little Bighorn defeat.

While there is quite a story to tell about the developments months later regarding Crazy Horse at the Red Cloud Agency and the government’s insistence that he visit Washington D.C. as a ceremonial measure or most likely for political purposes, that is another interesting tale for another time. The story that developed after the surrender of Crazy Horse and his eventual killing in September of 1877, only about four months after his surrender, is about as complicated as was the historic surrender itself and quite controversial.

(Photos are from the public domain)