Who Would Have Thought?

Everyone has heard of avalanches and how dangerous they are. Avalanche disasters have taken place in the Alps and other very high mountain chains for centuries. Several years ago when I first read about a catastrophic event that occurred in 1910, I was quite surprised that such an avalanche disaster could occur involving a passenger train. Who would have thought that the most deadly avalanche in United States history would involve a passenger train? Who would have thought it would have happened in the 20th century?

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!

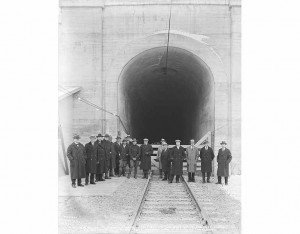

It was a well known fact that mountain snow drifts and potential avalanches were a problem for the railroads. The Great Northern trains and their mountainous northwestern route was no excepetion. The subject really came front and center as early as the late 1860’s while the nation was completing the transcontinental railroad. The toughest segment of that line was the route over the Sierra Nevada Mountains and Donner Pass being constructed by the Central Pacific Railroad. During that time, the Central Pacific’s chief survey engineer, Theodore Judah, was the man tasked with the problem. Judah devised a series of tunnels which cut through various mountain sides. In addition to those, Judah had constructed a series of snow sheds. The snow sheds, while not really being constructed due to potential avalanches as such, were built to keep the snow from drifting over the rail tracks at certain points. The snow drifts in the Sierra Nevada range in the vicinity of Donner Pass were legendary. If the Central Pacific was to offer reliable service, the snow drift problem had to be solved. The tunnels and snow sheds seemed to be the solution.

The tunnels and snow sheds, while rebuilt, are still in use today on this major rail line. Today, this route is traversed by Amtrak’s California Zephyr which runs on a daily basis between Chicago Illinois and Emeryville California, just across the bay from San Francisco.

The Magnificent Route of the Great Northern Railway

The Great Northern Railway was a transcontinental route that was built out from the twin Cities of Minnesota all the way westward to Seattle Washington. Needless to say, this route was quite scenic. One of it’s most scenic areas was just to the south of Glacier National Park. In fact, the Great Northern Railway marketed this National Park on posters, newspaper advertisements, etc. Glacier National Park was a tourist draw and it brought many passengers to the Great Northern trains. The Great Northern Railway promoted Glacier National Park much the way the Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe promoted the southwest, the Grand Canyon and the Harvey Houses. During the days before the automobile, the train was the way for curious travelers to see the wonders of the west. Western states saw a big boom in travel just after the turn of the century. People who could afford it took the train.

Rail Lines Through the Mountains

The Great Northern Railway overcame the mountain difficulties much the same way as the Central Pacific. They built a lot of tunnels. The Cascade Mountains of Washington state could dump a lot of snow. Avalanches were a real threat in the Cascades and they stopped traffic along the line many times. Avalanches are somewhat hard to predict. Snow can be sent sliding down a mountain side by a sound.

A train whistle, a gun shot, thunder, all can start the snow moving. The winter of 1910 was a heavy snow season and the Great Northern trains had to contend with several severe avalanches.

February 1910

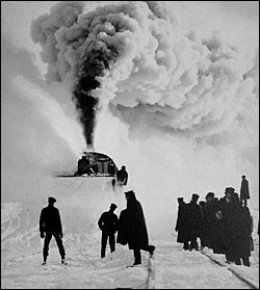

February 1910 was a month of heavy snowfall in the Cascades. For nine continuous days in late February, the small railroad town of Wellington Washington received very heavy snows. Often it was blizzard conditions. The work crews at Wellington worked hard just to keep the tracks open. Extra crews were added. Reports were that about a foot of snow was falling every day and on one day alone, an enormous eleven feet. Interestingly enough, the railway used snow plows to try to clear the tracks. The snow plows were essentially locomotives with a fan blade on the front end to clear away snow. While these snow blowers as such could be quite effective, the amounts falling in the Cascade Mountains in late February 1910 were often too much for even these powerful engines. The snow plows would become stuck. Their blades clogged with snow. The snow was piling up that high and that fast. The snow plows effectiveness did have it’s limits.

March 1, 1910

Like most historic disasters, what occurred in Wellington Washington on March 1, 1910 was a combination of events that ended in disaster. If just one circumstance may have been different, the end result probably would have been much less deadly.

Due to avalanches along the area near Stevens Pass, just to the west of Wellington, train traffic was at a standstill. Two trains, a passenger train and a fast mail train running from Spokane to Seattle, were both stopped at Wellington. They could go no further west due to track blockage. To give you some perspective of the blizzard, the passenger train had been in Wellington for about a week. That train had been backed up into the Cascade Tunnel which was just east of Wellington.

The tunnel provided some relief from the elements. After several more snow slides occurred, many of the passengers demanded that the train be brought back out of the tunnel for fear of being trapped inside if a snow slide should cover the tunnel entrance. The passengers were panicking. This the railroad did although they originally backed into the tunnel to avoid avalanches in the first place.

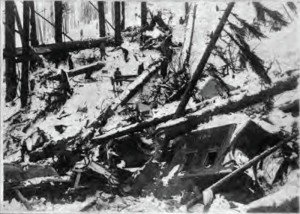

After the train emerged from the safety of the tunnel, it could go no further than the depot at Wellington. There it stayed behind the mail train. The passenger coaches were now below a mountain ridge on one side and the Tye Creek on the other. The avalanche that ended up sweeping both the Spokane Express and the Fast Mail train down a 150 foot ravine happened in the middle of the night of March 1st. What caused this massive Wellington avalanche that destroyed two trains is not entirely certain. Weather in the high Cascades can be tricky. Along with the snowfall was a lightening storm. Most believe today that either the thunder or lightening or both was the cause of the snow slide. Along with the trains, a portion of Wellington itself was thrown down the mountain side. It was later estimated that a ten foot high and half a mile wide snow drift slid through the town and pushed the two trains down the ravine.

The Next Day

The mail train did not carry passengers and not all passengers were on the Spokane Express train when the great avalanche struck. Some had gone into Wellington for food and a degree of relaxation. How many days can one be stuck in a train car? Unfortunately, being off the train didn’t prevent some casualties. It was thought that at the time of the avalanche, 40 passengers were on the train in addition to 30 railroad workmen who had been sleeping in some of the coach cars. The other fatalities would have been people, both passengers and workmen, on the ground in Wellington.

Relief trains had a difficult time trying to reach Wellington disaster site because of blocked tracks. The rescue effort had to be carried on by foot. The official death toll was put at 96. There was speculation that the death toll may have been higher due to extra railroad workmen being involved.

There were a great many additional people around Wellington at that time working to clear the tracks.

Who Was to Blame?

Railway history was changed forever after March 1910. When this tragedy was investigated, there were many questions to answer. What could the Great Northern Railway have done to prevent what occurred? Was it unavoidable or was it just a random act of nature?

There was no doubt that the Great Northern took precautionary measures by backing the passenger train into the Cascade Tunnel. This was done to try to avoid what actually did happen. The passengers were also correct in being concerned that the tunnel entrances themselves might be sealed by an avalanche. Their begging that the train be moved forward out of the tunnel was not unreasonable. The fact that the passenger train could not have moved more forward because of the stuck mail train in front of it was nobody’s fault. It was just a fact of the situation. The Great Northern could have evacuated the train completely and had all passengers lodged in the town. This may have been impracticable due to available accommodations and as we later saw, the small town of Wellington was largely swept away as well. In hindsight, over one hundred years later, it seems that the best route of action would have been for the passenger train to have remained in the Cascade Tunnel. There would have been casualties from anyone staying in the town, but the disaster probably would have been much less fatal. By the same token, the passenger’s concern of being trapped in the tunnel was also rational. The Wellington Washington avalanche disaster of March 1, 1910 appears to have been an unfortunate chain of events that put many people in harms way simply because the options were few and the anxiety was great.

The very last of the bodies were not retrieved until some five months later. The Great Northern Railway began building several concrete snow shelters in October of that year. Ironically, the summer of 1910, after a rough snowy winter, also saw one of the worst forest fires in United States history. The areas of Montana, northern Wyoming, Idaho and British Columbia were devastated during what was called the Great Fires of 1910. It was also referred to as the Big Blowup or the Big Burn. That fire destroyed about three million acres and killed 87 people. The fire didn’t end until a cold front finally brought in steady rains.

Wellington Washington Today

The Great Northern Railway renamed the town to “Tye” not long after the tragedy. Tye is the name of the nearby creek. Today, there is no town or settlement at the site. A new tunnel was constructed in 1929 on another grade that is still in use today. The grade of the old route of the Great Northern Railway has been turned into a day use hiking trail. The “Iron Goat Trail”, was named after the logo of a goat used by the old Great Northern Railway. The trail is closed to bicycles, stock animals and motor vehicles. You can reach the trail head off the Old Cascade Highway at it’s intersection with the USFS Road 050. Turn right on the USFS road and drive forward to the trail head parking lot. The three mile long lower grade between Scenic and Martin Creek is free of barriers and wheelchair-accessible.Much more information is on the trail’s web site www.irongoat.org/hike.html The trail obviously goes through some very scenic country and is a popular route for hikers.

(Photos from the public domain)