The USS Pampanito Goes to War

Between 1944-45 the Pampanito completed six war patrols in the Pacific Theater. After her shakedown cruise in the Atlantic, the USS Pampanito headed directly for Pearl Harbor via the Panama Canal and arrived there in February 1944. Her deployment was during the latter part of the Pacific war.

When you tour the USS Pampanito you will get a good feel of the last few years of the war. This was the period after the Battle of Midway when the U.S. was quite on the offensive in the western Pacific. Her first war patrol took her to Saipan and Guam. She had to return to Pearl Harbor for repairs of damage caused by Japanese depth charges. An interesting thing when you tour the Pampanito today are the separate displays of items such as depth charges, torpedos (shown above right) and torpedo hatches. Your visit to the vessel is more than just a tour of a submarine. It’s really a well rounded presentation of World War Two submarine warfare in general.

The Patrols of the U.S.S. Pampanito

The Pampanito’s second war patrol took her near the Japanese home islands where she almost was almost hit by torpedos from a Japanese sub. Her third patrol was in the South China Sea where she inadvertently sunk a Japanese troop ship which was transporting British POW’s. This was quite common of the Japanese to bring some POW’s back to the home islands. The Pampanito picked up over 70 survivors of that sinking. The fourth patrol was off Formosa where she sunk a 1,200 ton Japanese cargo ship. The fifth patrol was in the Gulf of Siam where another cargo vessel was sunk and then back to the Gulf of Siam for her sixth patrol.

After the sixth patrol the USSA Pampanito sailed back to Pearl Harbor then on to San Francisco for an overhaul. She then went back to Pearl Harbor but was called back to San Francisco because of the war’s end.

Decommissioning

The USS Pampanito was decommissioned at Mare Island next to the North Bay town of Vallejo California in December 1945. It’s not far east of Vallejo in the Sacramento River where the Navy stored many old World War Two vessels in what was called the “mothball fleet“. The question is…what does a perfectly good submarine do after the war and after being decommissioned? Not a whole lot until 1962 when the Pampanito was assigned as a Naval Reserve Training Ship at Vallejo. Finally in December 1971 the USS Pampanito was officially taken off Navy registration records, almost thirty years after the launching of this historic United States naval ship.

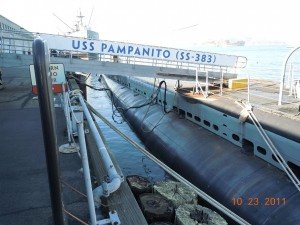

Today, the USS Pampanito is on the National Register of Historic Places and is an official National Historic Landmark.

Just as the ship berthed behind her, the Jeremiah O’Brien, the Pampanito was recognized as being an invaluable asset perfect for historic preservation and for the public to enjoy and learn from. While the Jeremiah O’Brien represents the all important Liberty Ship program, the Pampanito represents the heroic contributions of submariners during war.

Visit the USS Pampanito

The USS Pampanito is now owned and operated by the San Francisco Maritime National Park Association which displays several historic ships.

The submarine was transferred to the Maritime Park Association in 1976 and was opened for public tours in 1982. When you visit the Pampanito you’ll pass the Maritime National Park which displays several more historic ships like the side wheeler Eureka which among other assignments ferried passengers and automobiles over San Francisco Bay during the early 1900’s.

If you enjoy exploring old vessels and World War Two naval ships, you’ll absolutely enjoy these displays adjacent to Fishermans Wharf at the San Francisco Maritime Park. It’s one of the very finest displays of maritime vessels in the United States.

See these additional Trips Into History articles on the links below…

World War Two Attacks on America’s West Coast

Today, this classic World War Two submarine also makes a great venue for group sleepovers. Organizations such as the Cub Scouts have taken advantage of this opportunity to spend the night on the Pampanito using it’s 48 bunk beds. Small waves churned up by passing cargo ships often give the Pampanito a slight roll so those who spend the night aboard may get an authentic sailing experience. The Pampanito also conducts educational programs for adults and youngsters.

Take a fascinating tour back to the times of World War Two and the U.S. Navy in wartime by visiting the magnificent floating museum which is the submarine USS Pampanito.

To get to the submarine on Pier 45 in San Francisco, walk straight through the Musee Mecanique (entrance shown at right) at Fishermans Wharf and turn left on the pier. At that point you will see both the Pampanito and the Jeremiah O’Brien behind her.

(Article and photos copyright Trips Into History)