Chester William Nimitz From Fredericksburg Texas

Fredericksburg Texas, in the middle of the beautiful Texas Hill Country, is one of the most popular stops for those on Texas vacations. Fredericksburg TX is a very unique and historic location with excellent restaurants (German fare is a big draw), beautiful and historic bed and breakfast lodgings and is the home of the Admiral Chester Nimitz Pacific War Museum.

Fredericksburg Texas, in the middle of the beautiful Texas Hill Country, is one of the most popular stops for those on Texas vacations. Fredericksburg TX is a very unique and historic location with excellent restaurants (German fare is a big draw), beautiful and historic bed and breakfast lodgings and is the home of the Admiral Chester Nimitz Pacific War Museum.

Chester William Nimitz was born on 24 February 1885, in Fredericksburg, Texas. Young Chester, while in high school and even though his grandfather was a retired sea captain, decided on a career with the Army. While a student at Tivy High School in Kerrville Texas, Chester tried for an appointment to West Point. Unfortunately no vacancies existed and Nimitz then took a competitive examination for the Naval Academy at Annapolis and was selected.

Chester Nimitz’ appointment to Annapolis in 1901 was from the Twelfth Congressional District of Texas. This was prior to his high school graduation. Chester Nimitz attended Annapolis and graduated the academy in the class of 1905. He graduated seventh in a class of 144.

Nimitz moved up through the Naval ranks and held a variety of positions including Commander of Cruiser Division, Commander of Battle Division and in 1939 was appointed as Chief of Bureau Navigation which was to last for four years.

A fast change in command occurred shortly after Pearl harbor. In December 1941, after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Nimitz was designated as Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas, where he served throughout World War Two. On 19 December 1944, he was advanced to the newly created rank of Fleet Admiral, and on 2 September 1945, was the United States signatory to the surrender terms aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

Chester Nimitz has been credited with supervising some of the early successes the U.S. enjoyed such as James Doolittle’s raids on Japan via a flight carrier as well as the victories in the Coral Sea and the Battle of Midway. At Midway, Japan lost all four of her aircraft carriers engaged in that battle. The Battle of Midway of course is another entire story in itself.

After World War Two

Chester W. Nimitz and his wife eventually moved to Yerba Buena Island in San Francisco Bay, between San Francisco and Oakland and home of the Treasure Island Naval Base. Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz passed away at his home on Treasure Island on February 20, 1966 at the age of eighty. He was buried at Golden Gate National Cemetery at San Bruno California, just south of San Francisco. He was the last surviving five-star admiral.

See the Trips Into History articles on the links below…

Touring the Texas Hill Country

The National Ranching Heritage Center / A Texas Treasure

Visit Luling Texas / Railroads, Oil and Watermelons

Visit the National Museum of the Pacific War

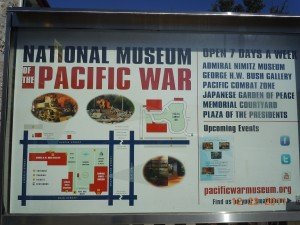

The mission of the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg Texas as stated on their website is “dedicated to perpetuating the memory of the Pacific Theater of WWII in order that the sacrifices of those who contributed to our victory may never be forgotten“.

The museum chronicles the story of Japan’s rise in military power, the beginning of World War Two in the Pacific and the advance of the Allied military to final victory in 1945. There are also very interesting exhibits regarding the home front and the war’s effect on both Texas and the nation. Many artifacts are on display including newspaper articles, and mementos. There are real guns, tanks, planes and even a submarine exhibit. You’ll see the “live” exhibits where real WWII veterans have recorded their stories for you to listen to, or you can hear a re-enactment of the bridge chatter on a cruiser during battle, or look through a simulated periscope.

The National Museum of the Pacific War traces the roots of the events leading up to World War Two. The museum really does an excellent job of sharing information about the causes of World War Two as well as the numerous details about the various aspects of the war. There is no other museum like the National Museum of the Pacific War.

Lots of interesting information about the Nimitz family is found which helps you place his accomplishments in context. The museum is quite large and three hours or even more might be set aside for a partial exploration. In reality, to take full advantage of all the unique exhibits, you might plan on a full day visit and possibly come back again the next day.

It’s very unique to have such a large museum available in a smaller town like Fredericksburg Texas. It’s a real treasure and a must see if you’re touring the scenic Texas Hill Country. The National Museum of the Pacific War is located at 340 E. Main St., Fredericksburg Texas.

Fredericksburg is located about 69 miles northwest of San Antonio and about 77 miles west of Austin.

(Article and photos copyright 2014 Trips Into History)