In the year 1849, would you have taken one family’s trek across North America? The chances are that you could have embarked on the journey, but the real question is “would you have?”. Learning about the trip from Oregon Trail diaries and narratives will help you decide. Hearing about the sacrifices and ordeals of such a journey from someone who made it is the best history narrative available. The Oregon Trail diaries and narratives are invaluable historic artifacts.

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!

In the very enlightening book, Women’s Diaries of the Westward Journey, by author Lillian Schlissel, there is a very vivid description of one family’s travels from Clinton Iowa to Sacramento California. The reason the trip was made were purely economic. There was gold in California. There was plenty of it but not quite the easy pickings that most stories that made it back to the midwest declared.

Why Head West?

One major reason that many families decided to risk a trip through hostile lands was the economic shape of the U.S. at that time. Most historical accounts, not all but most, ignore the real driver of this emigration. That was the Economic Panic of 1837. Just like today, there were economic panics that placed many in rough economic shape. In fact, this economic collapse depressed farm real estate prices well into the 1840’s. It wasn’t a one or two year event. Many merchants lost their businesses or owed a considerable amount to creditors. To say the California Gold Rush was talked about is an understatement. Our history books tells us that it was THE subject being discussed everywhere in America during 1849. People asked their neighbors and friends if they would be making the journey. Advice was given out freely. Some of it good and some of it not so good. You can imagine just how exciting the prospect was for a new start in life and the possibility of riches in a backdrop of national economic weakness. What exactly would it take to make the decision to risk everything for possible riches? Even if the risk didn’t result in riches, which for most it didn’t, would the journey through America’s wilderness in a covered wagon still be worth it? Many people in 1849 thought it was.

The family chronicled in this particular diary and narrative were newlyweds with the husband being a lawyer by trade. They ran into financial difficulty like many others. Also, like many others, they were hearing incredible stories from California. In the case of this particular family, their desire to go to California, which they termed the new El Dorado, was to acquire enough gold to return to Clinton Iowa and pay off their creditors. A return trip to Iowa at some future date was always part of the plan. The Oregon Trail beckoned. It was the shortest way to California from the jumping off towns. Whether for economic reasons or time frame, a voyage to California by ship was not realistic.

The majority of the Oregon Trail travelers in 1849 were midwesterners. Those from the eastern seaboard states that wanted to get themselves to California often went by ship whether around Cape Horn or through the isthmus of Panama.

Assembling in Council Bluffs Iowa

When the decision was made to head west, the family left with four wagons. Two of the wagons were filled with merchandise that they would sell at enormous profits when once reaching the remote gold fields. The profits were there to be made if only you could reach California. In 1849 there were three main jumping off points as they were called for those heading west. They were Council Bluffs Iowa, St. Joseph Missouri and Independence Missouri. These are the points where people convened to join wagon trains. It was where you might spend some time beforehand acquiring what supplies you hadn’t already. The journey to Council Bluffs of course was the easiest segment. You could camp near farmhouses, easily purchase needed food supplies and the terrain was flat and green. For obvious weather reasons, journeys started in April after the winter snows melted. Understanding that the journey might very well take at least six months, an April start was necessary to avoid the Sierra Nevada snowstorms in the fall. The launching off from Council Bluffs Iowa most likely would begin in May. The diary and narrative excerpts of this 1849 journey were kept by Catherine Haun, who with her husband and five other men and a female cook, set out from Clinton to Council Bluffs Iowa and from there into what was referred to as the wilderness. To an Iowa family in 1849 it was the great unknown.

The notes taken by Mrs. Haun point out that there were certain attributes looked for when joining a wagon train. First was that there was an ample supply of firearms and ammunition. Secondly, that the train’s wagons were not loaded so full that they would hinder travel time. Animals needed to be sturdy whether they were oxen or horses. Oxen were preferred because they were considered less likely to stampede and were less likely to be stolen by Indians. Indians wanted horses, not oxen. Good general health was also a benefit and you didn’t want a caravan with a disproportionate amount of women and children. Of course all the planning in the world could not totally isolate one from the surprises and dangers of the wilderness. When all was said and done, the caravan which included the Haun party consisted of seventy wagons.

Indians

The biggest concern seems to have been the possibility of Indian attack although it was thought of more than spoken about. Mrs. Haun writes that the bucks with their bows and arrows, buckskin garments and feathered headgear followed the wagon train regularly. They were relatively friendly yet were to beg often at mealtimes. She wrote that they seldom molested any of the whites. Catherine Haun does write that throughout their journey the Indian presence still caused anxiety. She was never sure of their friendship and being alert was a necessity. She writes of instances where Indians crept into their camp at night and stole items such as blankets. Mrs. Haun describes how their soft moccasins made it hard to hear their presence. The fact that Indians could enter a campsite undetected was itself alarming to the wagon train party. Compared to what some pioneers endured the Haun caravan seemed fortunate. Mrs. Haun notes in her diary that after the wagon train passed the prairie lands, the Indians appeared to be more treacherous and numerous. At night, for protection, the caravan would draw their wagons in a circle. When they determined where they would spend the night, one wagon would go left, the other to the right and so on and so forth until they had a circle with a good size area in the middle.

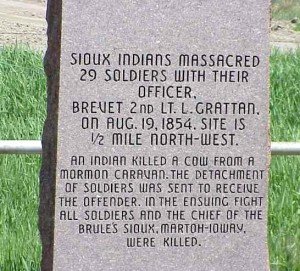

It should be noted that the year the Haun’s journeyed to California was not nearly at the height of Indian trouble on the Oregon Trail. The real trouble appeared to start between 1854 and 1860 when a large number of army troops were sent east to fight the Civil War. At the same time there were disputes between the U.S. government and Indians regarding emigrants and promised annuities. This led to increased Indian attacks throughout the plains and down into Texas. Many times, wagon trains were the targets.

Sickness

Emigrant deaths along the Oregon Trail stemmed from many causes. Accidents, drownings and sickness being the major ones. Indian attacks would not be significant causes. There may have been no larger single cause of death among the Oregon Trail pioneers than cholera. The chief cause of cholera was bad water and the sickness was highly contagious. Catherine Haun points out the enormous number of graves, some fresh, that their wagon train passed along the Oregon Trail. One of the reasons that exact estimates of cholera deaths on the Oregon Trail is hard to determine is that the custom was to bury many people in unmarked graves. This was to avoid having them dug up by Indians or wild animals. Mrs. Haun notes that their caravan passed a grave which had been opened by Indians in order to get at clothes. Many suppose this also caused the Indians to pick up the dreaded disease. It’s been written that cholera may have killed up to 3% of all Oregon Trail travelers during the epidemic years of 1849 to 1855.

Rivers

Wagons could cross rivers on their own if the water was shallow enough. If not, they would be rafted over to the other side but not before removing their wheels so that they would lie flat and not tip over. Not an easy job in any circumstance.

Before trying to drive your wagon pulled by oxen over a river you would need to be sure the bottom wasn’t quicksand. This was a problem with several river crossings and there was more than one wagon lost to the river bottom.

The Mountains

There was a reason the short lived Butterfield Overland Stage Line ran through Texas and the New Mexico Territory in 1858. Less high mountains. Much of the Butterfield Stage route traveled over desert. What mountain passes that were encountered were nothing like the Sierra Nevadas in California. Imagine trying to manage wagons, teams of oxen and horses, not to mention people, over some of the most formidable mountain passes in North America. Everyone was aware of the fate of the Donner Party in the Sierra Nevada winter of 1846.

When the trail reached steep inclines and declines, people had to join in to keep the wagons going uphill, and when they started a descent, ropes behind the wagons needed to be pulled by as many people as possible to keep the wagon from crashing into the oxen in front.

Following is an excerpt on this subject from Catherine Haun..”and oh, such pulling, pushing, tugging it was! I used to pity the drivers as well as the oxen and horses-and the rest of us. The drivers of our ox teams were sturdy young men, all about twenty-two years of age who were driving for their passage to California”.

Passing the Time

It’s a fact that most wagon trains tried to start moving before 6 AM. As a consequence most people didn’t keep late hours. Catherine Haun describes the evening hours…” We did not keep late hours but when not too engrossed with fear of the red enemy or dread of impending danger we enjoyed the hour around the campfire. The menfolk lolling and smoking their pipes and guessing or maybe betting how many miles we covered the day. We listened to readings, story telling, music and songs and the day often ended in laughter and merrymaking”.

The Haun’s wagon train reached the Laramie River on July 4, 1849. Mrs. haun goes on to describe some of things planned for that special day. ” After dinner it was proposed that we celebrate the day and we all heartily joined in. America West was the Goddess of Liberty, Charles Wheeler was orator and Ralph Cushing acted as master of ceremonies. We sang patriotic songs, repeated what little we could of the Declaration of Independence, fired off a gun or two, and gave three cheers for the United States and California Territory in particular!”. (California would gain statehood one year later).

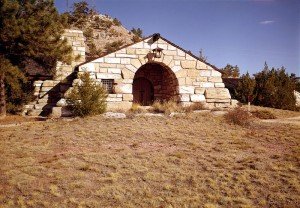

Two related articles regarding the Oregon Trail which you should find interesting are Lake Guernsey State Park Old Wagon Wheel Ruts and Fort Kearney and the Oregon Trail.

Summing Up the Overland Journey

Catherine Haun wrote down her feelings about the after they reached California. She wrote…”Upon the whole I enjoyed the trip, spite of it’s hardships and dangers and the fear and dread that hung as a pall over every hour. As though not so thrilling as were the experiences of many who suffered in reality what we feared, but escaped, I like every other pioneer , love to live over again, in memory those romantic months, and revisit, in fancy, the scenes of the journey.

As it turned out, the Hauns did not strike it rich in the California gold fields. Someone was calling for a lawyer to help draw up a will. Mr. Haun offered to do it for the man for a fee of $150. With the money Mr. Haun earned he bought lumber to construct a home. After that he dropped any idea of working the gold fields and hung out his lawyer shingle. Mrs. Haun noted that they had gamblers on one side of the house (they gave them the property to build on) and a saloon on the other. She goes on to conclude that she never received more respectful attention than she did from those neighbors.

As mentioned previously, the Hauns were fortunate to have traveled over the Oregon Trail before major problems developed with the plains Indians. Clashed leading to much bloodshed occurred starting in 1854 around Fort Laramie Wyoming and generally escalated with fits and starts into what is commonly referred to as the Plains Indian Wars. They led up to Custer’s Battle of the Little Bighorn and beyond. Most historians believe the Indian Wars ended for good with the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890. Wagon trains that journeyed over the Oregon Trail and connecting trails after 1854 and especially after 1860 and beyond were regularly attacked. The attacks were also much more violent as opposed to the harassment in the late 1840’s and early 1850’s. The level of warfare between the U.S. Army and particularly the Sioux and Cheyenne bands grew in violence up through George Armstrong Custer’s expedition in 1876.

Again, the question is… knowing, or perhaps not knowing, what the wilderness between Iowa and California had in store during the gold crazed year of 1849, would you have elected to make this journey?