The Grattan Memorial

There is a memorial in present day Goshen County Wyoming that many historians would say commemorates the very beginning of the Plains Indian Wars. What is known as the Grattan Massacre ushered in a quarter of a century of Indian warfare along the Great Plains of the western U.S.

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!

The marker shown in this article is located about 1/2 mile to the southeast of where the massacre occurred on August 19th, 1854. The marker is along Route 157 about 5 miles west of Lingle Wyoming.

At the time of the massacre, the battle site was east of Fort Laramie in Nebraska Territory.

A small detachment of U.S. Cavalty entered a Sioux camp and when it was all over a total of twenty-nine soldiers were killed plus a Lieutenant John Grattan and an interpreter.

The Ignition of Hostilities

Historians occasionally debate as to what represented the start of the plains Indian Wars. The Indian War was not one contiguous event but more of a decades long conflict with fits and starts and interspersed with weak treaties. History pretty much describes an escalating conflict that grew more violent and more fierce as more and more settlers traveled through traditional Indian lands. Of course, along with the settlers and emigrants heading to California and Oregon, so did the U.S. military increase it’s presence. In a very real way the Indian Wars were an event just waiting to happen. What was the spark that set it off? Was it a relatively small event that escalated into something much larger?

The Dakota War of 1862

The question then could be...just when did these hostilities begin? What was the beginning of the Indian Wars? In particular, what set off the Plains Indian Wars?

One answer often suggested is the very bloody Dakota Indian war in the state of Minnesota that occurred in August of 1862 right in the middle of the American Civil War.

The Dakota Indians residing in Minnesota were from the eastern band of the Sioux. Leading up to the war and one of it’s causes was something that would plague Native American-U.S. government relations for years to come...late or unfair annuity payments of supplies as per treaties in force at the time.

White traders had something to do with this as well since they were making demands to the government to send the annuity supplies to the Indians through them. The Dakota’s on the other hand wanted the supplies directly from their Indian agents, not from the traders. Everything reached a standstill.

In this unhealthy atmosphere, four young Dakota Indians came upon a farmhouse and were allegedly caught stealing some eggs. One thing led to another, and there are various variations of the story, but when all was said and done, five whites at the farm were killed by the Dakota youths. This event alone would have caused certain retaliation but to make matters worse, that very night a Dakota tribal council agreed to go to war against the whites and drive them out of the entire area of southwestern Minnesota. The bloody conflict went on for several months and only ended when the U.S. Army intervened and caused the surrender of most of the Dakota Sioux.

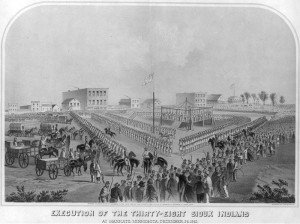

There are no reliable numbers of how many white settlers were killed at the hands of the Dakota Sioux, but most estimates say several hundred and some as high as 800. In December of 1862, an event never seen before or after occurred when the largest mass hanging in U.S. history took place. This occurred in Mankato Minnesota on December 26, 1862. A total of thirty-eight Dakota Sioux were hanged in front of a large crowd. After the U.S. government shut down the reservations in the spring of 1863, the Dakota Sioux were formally thrown out of the state and wandered westward to what is today Nebraska and South Dakota.

Trouble on the High Plains of Wyoming

What often is overlooked as the start of the Plains Indian Wars is what occurred just outside of Fort Laramie some eight years prior to the Minnesota Dakota War. What should have been a relatively routine event in the year 1854 exploded into the history books as one, if not “the” turning point in how Native Americans would be dealt with by the federal government for decades to come. This 1854 event marked the beginning of the Plains Indian Wars.

Additional articles we’ve published that you’ll find interesting are a Frontier Soldiers Life…Excerpts from the Oregon Trail Diaries…and the Fetterman Massacre.

On our Western Trips site, see the articles The Battle of Slim Buttes and the Steamboat and an Indian War.

A Mormon and his Slain Ox

The story starts with a Mormon pioneer making a complaint to the commander of Fort Laramie. The complaint as filed was that one of his oxen was killed by an Indian. The Mormon emigrant was traveling along the Oregon Trail and his ox apparently wandered away. The emigrant was certain that it was killed by one of the Sioux camped nearby. Handling of something like this would normally be the duty of the assigned Indian agent. It was not thought of as being a military matter.

The Indian agent was due in several days with annuities. In the meantime the owner of the ox was demanding an immediate $25 payment. The local Sioux Chief Conquering Bear tried to negotiate unsuccessfully.

At this point the military ordered the chief to bring the guilty Indian, who was identified as a Miniconjou, in to the fort. This is where things started to get out of hand.

The chief refused because he said he had no power over the Miniconjou’s. With things at a dead end in the affair, the military dispatched a young officer, Second Lt. John Grattan, to go to the Miniconjou Sioux camp and retrieve the wanted Indian. Lt. Grattan rode to the camp with twenty-nine armed soldiers. The task was to be relatively simple…arrest and bring the accused Indian back to Fort Laramie.

Similar to other historic events, the real details often come out sometime later as told by those who witnessed them. Sometimes they conflict but you can usually get a general idea of what took place.

In this particular confrontation most interpretations paint a picture of a relatively inexperienced young officer leading his heavily armed troops to the camp of the Miniconjou’s bent on returning with the accused Indian. During what turned into a standoff, one of the troopers apparently shot the Chief Conquering Bear. At that point the Indians attacked the small detachment of soldiers and killed all of them. It happened that quick.

Much of the descriptions of this event were related by a James Bordeau who owned a nearby trading post. Bordeau witnessed the massacre. Bordeau placed some of the blame on the interpreter brought along who he claimed taunted the Indians prior to the violence. Bordeau escaped with his life only because he was married to a Sioux and was also on very friendly terms with the tribe. Regardless, his trading post was cleaned out by the frenzied warriors.

In the aftermath of the massacre, some warriors rode to Fort Laramie determined to attack what they knew to be a lightly defended post. They ultimately withdrew without an attack and then moved their camp to the north knowing full well that some form of retribution would be coming.

Outcry From the Press

Outrage hit the streets when the press reported the Grattan Massacre. The description “Grattan Massacre” was the exact headline used in newspapers throughout the east. Newspaper reporting during the westward migration embraced the policy of Manifest Destiny. Stories often times were greatly embellished to help sell papers in a competitive environment, however the outcome of the Grattan Massacre was evident to all. What the press did was just throw lots of fuel on the fire.

Outrage Throughout the Nation

People were riled and tempers were flaring. The outrage wasn’t only in towns and cities but reached all the way up to President Pierce in Washington. Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis, characterized the massacre as being preplanned and vowed a strong military response.

The military response did come about one year later headed by General William S. Harney. Harney, a southerner and later a Confederate soldier, led a scorched earth policy against the Sioux. Harney was looking for retribution, not parley, and one result was the wiping out of an entire Lakota Sioux camp in a raid known as the Battle of Ash Hollow and sometimes called the Battle of Bluewater Creek. The infantry pinned the Sioux down between themselves and the cavalry. Women and children were caught in the crossfire.

Dozens of prisoners were also taken back to Fort Laramie and some sent back to Fort Leavenworth Kansas. General Harney was able to put together a treaty with the tribes a year later which was on strictly U.S. Government terms but as with many treaties agreed upon and signed years later, they usually weren’t lasting.

Historic Sites to Visit

The bodies of Grattan and his troops were recovered and buried. Later they were reburied and memorial markers built. The troops were formally buried at Fort McPherson National Cemetery in Lincoln County Nebraska and that of Lt. John Grattan at Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery in Kansas.

The Grattan Massacre in 1854 and it’s aftermath however was recognized as the first time the U.S. federal government officially set out against the plains Indians in a retaliatory mission. The military mission in 1855 was to answer the opening salvo which took the form of the Grattan Massacre. Many expeditions would follow in the ensuing decades.

From that point forward, through Red Cloud’s War in the late 1860’s and the resulting Fetterman Massacre, the Sioux War of 1876-77 and the Custer defeat, and then years later to the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890, conflicts took place on and off with various Native Americans of the Great Plains. The Plains Indian War was a war that raged on and off for almost four decades.

It all began with the Grattan Massacre on August 19th, 1854 in Nebraska Territory.

(Article copyright 2013 Trips Into History. Photos and images in public domain)