The Columbia River was and still is the aorta of the American Northwest. Along with it’s tributaries such as the Snake and the Williamette, the famed Columbia River stretches for thousands of miles. What was once a mighty river that needed to be tamed now is a mighty river that Oregon tourists enjoy continually. Riding up the Columbia River to the beautiful Columbia Gorge and viewing the scenery that Lewis and Clark did is a fascinating trip into history. A Columbia River map will show you just how large this river is. The Columbia River has a rich history that the following story will help tell.

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!The Columbia was recognized very early on by the Native Americans to be a highway through otherwise difficult and sometimes impossible terrain. The Columbia ran it’s course through jagged mountains and remote flat lands. This amazing river spread so far to the east into Montana and Idaho that it almost converged with the Yellowstone River which flowed in an opposite direction. A some points, a rain drop could run in either direction, west to the Pacific Ocean or eastward down the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers to the Gulf of Mexico near New Orleans. The Columbia River of course made it possible for Lewis and Clark to reach present day Oregon.

One of the best ways to fully understand the significance of the Columbia River and learn what it took to make it a navigable route, is to take a glimpse into the life and feats of one of it’s very first river pilots. This man was named Captain John C. Ainsworth ( pictured left) and many referred to him as the “King of the Columbia River Steamboatmen”. He arrived in Oregon in 1850.

One of the best ways to fully understand the significance of the Columbia River and learn what it took to make it a navigable route, is to take a glimpse into the life and feats of one of it’s very first river pilots. This man was named Captain John C. Ainsworth ( pictured left) and many referred to him as the “King of the Columbia River Steamboatmen”. He arrived in Oregon in 1850.

Like many experienced steamboat men, John Ainsworth gained his river piloting skills along the Mississippi River. He recognized the opportunities present in the northwest. Fellow steamboatmen would ask John Ainsworth the question…why would a skilled river pilot waste his time in the relative wilderness of Oregon when there was plenty of money to be made down in California?

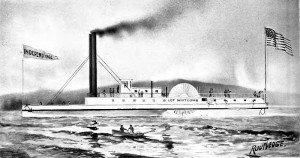

Ainsworth had the good fortune at the time to meet a man by the name of Lot Whitcomb (pictured below right). What Whitcomb didn’t have in knowledge of piloting a steamboat, he did have in industriousness. Whitcomb was buying up materials to construct the first home built steamboat made in Oregon. The boat that Lot Whitcomb would build was named, unsurprisingly, after himself, the “Lot Whitcomb”.The vessel was 160 feet long with a 24 foot beam, two boilers producing 140 horsepower and capable of 12 MPH on the open river. It was a sidewheeler boat. The Lot Whitcomb steamboat was roomy, had a dining room and an interior of polished wood. Whitcomb’s new vessel offered elegance in the wilderness. It was the best looking boat in Oregon.

The steamboat was built simply because Lot Whitcomb believed in the potential for steamboats in the northwest just as John Ainsworth did. Whitcomb eventually offered the job of commanding his new steamboat to Ainsworth. He accepted. Unfortunately, the two found out they didn’t get along too well. Most historians attribute this to the fact that Whitcomb could have been envious of Ainsworth steamboat piloting abilities. He knew river navigation much better than Whitcomb. Regardless, John Ainsworth stuck it out with Whitcomb and kept envisioning the potential for himself to operate a fleet of steamboats on the very river that Lewis and Clark in 1804 used to explore to the Pacific Ocean. relations with Whitcomb didn’t improve and as far as Ainsworth was concerned it was only a matter of time that he would leave and strike out on his own. The problem however was money. Ainsworth didn’t have the needed funds to begin his own operation. His plan was to convince fellow Oregonians to fund an able steamboat captain like himself. He would need to convince them of the economic potential of Columbia River steamboating. As time went on and John Ainsworth was piloting on the Columbia River the population was growing. That also meant that the commerce was growing. Competition from other boats grew and Ainsworth had the uncomfortable thought that perhaps some other experienced boat men from the Mississippi would emerge and steal his dream.

A strange thing happened shortly after the official brass band accompanied launch of the Lot Whitcomb ( sketch at left). The steamboat got itself hung up on a reef. At first, people who heard the news blamed Ainsworth, but as it turned out, he had taken the day off and the boat was piloted by none other than Lot Whitcomb himself and an assistant. Whitcomb of course called Ainsworth for help in freeing the vessel at which he flatly refused. he didn’t want to get aboard until the boat was back where he left it. The story is that Whitcomb had spread rumors that the hang up was Ainsworth’s fault even though he was nowhere near the accident scene. The rumors started to tarnish Ainsworth’s reputation as an excellent steamboat pilot. That signaled the end of the association between the two men. Ainsworth received a payment of $3,500 for his time with Whitcomb. At the same time Whitcomb had severe financial problems and sold had to give a controlling interest to an Oregon City Company. Ainsworth stayed on piloting the “Lot” and plowed his money back into the steamboat. For this he received a share of the ownership. In 1854 the Lot was sold for $40,000 and was to be sent to work on the Sacramento River in California. Ainsworth received $4,000 from the sale as his ten percent share.

A strange thing happened shortly after the official brass band accompanied launch of the Lot Whitcomb ( sketch at left). The steamboat got itself hung up on a reef. At first, people who heard the news blamed Ainsworth, but as it turned out, he had taken the day off and the boat was piloted by none other than Lot Whitcomb himself and an assistant. Whitcomb of course called Ainsworth for help in freeing the vessel at which he flatly refused. he didn’t want to get aboard until the boat was back where he left it. The story is that Whitcomb had spread rumors that the hang up was Ainsworth’s fault even though he was nowhere near the accident scene. The rumors started to tarnish Ainsworth’s reputation as an excellent steamboat pilot. That signaled the end of the association between the two men. Ainsworth received a payment of $3,500 for his time with Whitcomb. At the same time Whitcomb had severe financial problems and sold had to give a controlling interest to an Oregon City Company. Ainsworth stayed on piloting the “Lot” and plowed his money back into the steamboat. For this he received a share of the ownership. In 1854 the Lot was sold for $40,000 and was to be sent to work on the Sacramento River in California. Ainsworth received $4,000 from the sale as his ten percent share.

John Ainsworth, now with his $4,000 to get started, befriended a Mississippi River man who was an excellent engineer, and they together made plans to build a sternwheeler for Ainsworth to operate. The boat envisioned was to be built and named the “Jennie Clark”. She would be 115 feet long and 18.5 feet at the beam. The boiler was centered on the vessel and the rudders were to be placed very near the rear paddlewheel to give maximum control. The Jennie Clark was built and launched in 1855 and didn’t take long at all to start making a profit with both passengers and freight. The story of John C. Ainsworth and his steamboat company only grew from here. The public domain image below is of Astoria, Oregon in 1868.

John Ainsworth and a group of investors incorporated the Oregon Steam Navigation Company in 1860. Ainsworth’s company was so large it controlled the shipping routes of steamers, railroads, and freight lines. It essentially became the biggest transportation monopoly in the Pacific.Northwest. The company also began operating steamers between San Francisco and ports along the Columbia River such as Astoria and Portland. By the year 1869 the OSN Company virtually controlled Columbia River traffic. Then, In 1872, Ainsworth exchanged a controlling interest in the OSN to the Northern Pacific Railroad in return for the railroad’s bonds.In less than twenty years John Ainsworth turned an idea and a dream into vast wealth. To be sure, it was the right idea at precisely the right location.

John Ainsworth and a group of investors incorporated the Oregon Steam Navigation Company in 1860. Ainsworth’s company was so large it controlled the shipping routes of steamers, railroads, and freight lines. It essentially became the biggest transportation monopoly in the Pacific.Northwest. The company also began operating steamers between San Francisco and ports along the Columbia River such as Astoria and Portland. By the year 1869 the OSN Company virtually controlled Columbia River traffic. Then, In 1872, Ainsworth exchanged a controlling interest in the OSN to the Northern Pacific Railroad in return for the railroad’s bonds.In less than twenty years John Ainsworth turned an idea and a dream into vast wealth. To be sure, it was the right idea at precisely the right location.

In April 1879, Henry Villard purchased the Oregon Steam Navigation Company for its full capitalized value of $5 million. Ainsworth then relocated to Oak Lawn, California, a very wealthy man. This was not however the last of Ainsworth business ventures. After selling out his shares in OSN, in 1883 he entered the banking business. Ainsworth founded the Ainsworth National Bank in Portland and later in 1892 he started the Central Bank of Oakland.

The Columbia River and it’s famed Columbia Gorge continue to marvel visitors. Today, tourists have the opportunity to ride up and down the river enjoying cruises lasting a week or longer or they can simply take a picturesque day cruise and get some great photo opportunities. Many people also enjoy the dinner cruises on the boat Portland Spirit. If you have the opportunity to do any of these things you just may want to remember the dream of John C. Ainsworth and the great success he had operating a fleet of steamboats.

John C. Ainsworth passed away on December 30, 1893 near Oakland California. He was seventy-one years of age.

(Photos and images are in the public domain)